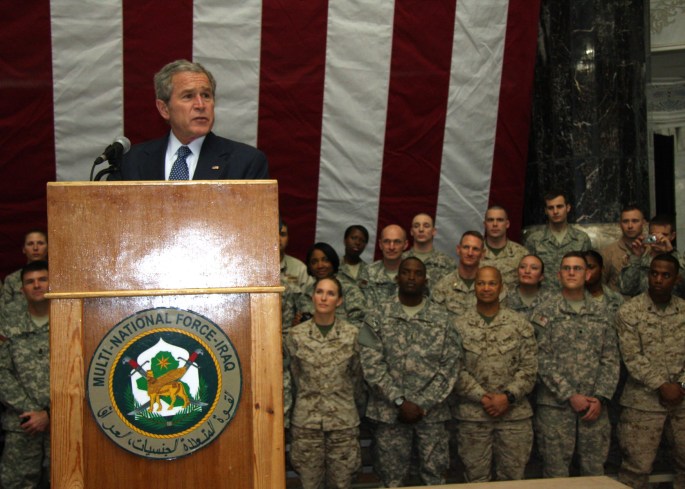

America’s goal to democratize Afghanistan started haphazardly, no doubt buffeted by the chaos of the days immediately following 9/11. However, what began as a relative afterthought soon became the perceived cure-all for Islamic extremism—bring democracy to the Middle East and watch the underlying causes of terrorism erode away. As the Bush administration began developing that policy, a fair amount of scholarly research and intelligence (now declassified) was available to assist policymakers.

This is Part 2 of 4 of Erik Goepner‘s paper. Read Part 1 here.

The pre-9/11 scholarly research

The pre-9/11 scholarly research could have helped answer two key questions:

- Would democracy be likely to succeed in Afghanistan and Iraq?

- Would a shift from autocracy to democracy in Afghanistan and Iraq help reduce the number of terrorists and terror attacks?

The research suggested that establishing a functioning democracy would be quite challenging in either country. Regarding democracy in Muslim states, ample research cautioned that many democracy enablers—cultural and institutional—could not be found within Islamic tradition.[1] Several notable scholars agreed obstacles existed, but they assessed them as surmountable.[2] Looking at democracy more broadly, the eminent democracy scholar, Seymour Martin Lipset, highlighted cultural factors as determinants of success, cautioning that culture is “extraordinarily difficult to manipulate.”[3] Seven years prior to 9/11, Lipset wrote that successful democracies in Muslim-majority countries were “doubtful.” He argued that an enduring democracy necessitated a connection between efficacy and legitimacy that could be observed by the population. Progress in either the political or economic arenas, he said, would build perceived legitimacy and help cement democracy.[4] With respect to Afghanistan in particular, Robert Barro observed that democracy was unlikely to take hold because of low education levels, the marginalization of women, and the patchwork of different ethnicities.[5] Fareed Zakaria stressed the potential problems associated with ethnic fractionalization and democracy, noting the chance of war could actually increase if democracy were introduced in a country that did not yet have a liberal culture or institutions.[6] Similarly, Amitai Etzioni, a former advisor to President Carter, noted the difficulties of a society jumping from “the Stone Age to even a relatively modern one.” He pointed to the failed experiences of the World Bank and U.S. foreign-aid programs, ultimately concluding that democratic failure would result in Afghanistan.[7] These observations highlight the tension between the legitimate aspirations of President Bush and his national security team and the numerous obstacles that the pre-9/11 research had already identified.

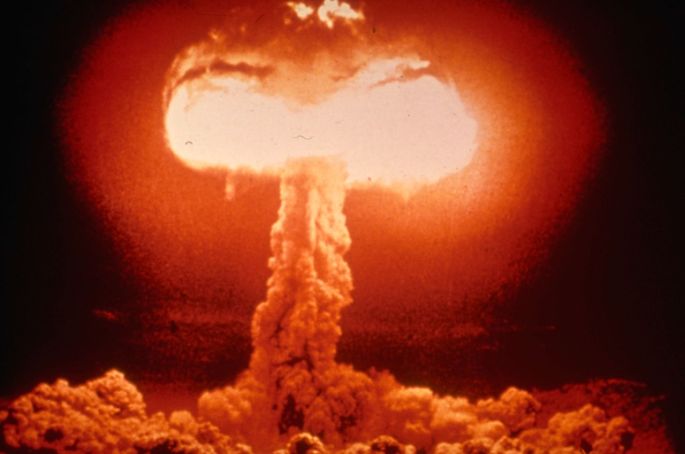

States in transition from autocracy to democracy have more political violence within their borders than do either strongly democratic or autocratic states. In terms of stable, entrenched democracies, the research is divided on whether democracy reduces terrorism more effectively than other forms of government or not. On the one hand, scholars like Rudy Rummel and Ted Gurr contend that democracies provide a system within which grievances can be non-violently addressed, whereas autocracies are much more prone to political violence because they deny their citizens alternate forms of political communication.[8] On the opposite side, researchers like Havard Hegre suggest that democracies are home to increased amounts of political expression, both non-violent and violent.[9] Empirical studies suggest developed and stable democracies do have lower levels of political violence, but so do harshly authoritarian states. Higher levels of political violence, however, tend to occur in intermediate regimes, such as infant democracies.[10]

Based on the pre-war intelligence

The Bush administration planned the Iraq War for more than a year, and authorities have declassified much of the pre-war intelligence. As a result, ample intelligence is now available to the public. Conversely, for the war in Afghanistan, essentially no intelligence regarding governance issues is available since the war came quickly after the 9/11 attacks and the military had no plans for Afghanistan until after September 11th (beyond tactical plans to attack bin Laden).[11] Much of the available intelligence regarding Afghanistan comes from the 9/11 Commission Report, but it does not include useful information for analyzing the decision to democratize. Therefore, only an analysis of the pre-war Iraq intelligence is provided.

The policy choice to promote democracy appears to have discounted significant portions of the pre-war intelligence. In August 2002, a CIA report noted that Iraqi culture has been “inhospitable to democracy.” The report went on to say that absent comprehensive and enduring US and Western support, the likelihood of achieving even “partial democratic successes” was “poor.”[12]

In late 2002, the CIA provided a slightly more optimistic assessment which said most Shia would conclude that a “secular and democratic Iraq served their interests.”[13] At the same time, though, a DIA report asserted that Shia preferences could not be accurately assessed because of the fear and repression they lived under.[14] Several months later, the CIA released another assessment indicating the potential for democratic stability would be “limited” over the next two years, but a US-led coalition “could” prepare the way for democracy in five to 10 years.[15]

Additionally, the National Intelligence Council (NIC) published two Intelligence Community Assessments in January 2003, which the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence described as the “best available ‘baseline’” of prewar assessments on postwar Iraq.[16] The reports described democratic concepts as “alien to most Arab Middle Eastern political cultures.”[17] The NIC also noted “Iraqi political culture does not foster liberalism or democracy.” As a result, they assessed the potential for the democratization of Iraq as a “long, difficult, and probably turbulent process.”[18] In a particularly prescient set of comments, the NIC assessed that “political transformation is the task…least susceptible to outside intervention and management.”[19]

Considerable scholarly research and intelligence were available to policymakers before the decision was made to aggressively pursue democracy in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the broader region. The numerous cautions contained in the intelligence and research, however, were either missed or ignored.

Next week, part 3 will examine the research published since 9/11 in light of the decision to pursue broad democratization. Erik Goepner’s full paper is available here.

[1] Alfred C. Stepan, “Religion, Democracy, and the ‘Twin Tolerations,’” Journal of Democracy 11, no. 4 (2000): 47.

[2] Niloofar Afari et al., “Psychological Trauma and Functional Somatic Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Psychosomatic Medicine 76, no. 1 (January 2014): 2–11; John Esposito and John Voll, Islam and Democracy (Oxford University Press, 1996).

[3] Seymour Martin Lipset, “The Centrality of Political Culture,” Journal of Democracy 1, no. 4 (1990): 82–3.

[4] Seymour Martin Lipset, “The Social Requisites of Democracy Revisited: 1993 Presidential Address,” American Sociological Review 59, no. 1 (February 1, 1994): 6, 17.

[5] Robert Barro, “Don’t Bank on Democracy in Afghanistan,” Business Week, January 21, 2002, 18.

[6] Fareed Zakaria, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy,” Foreign Affairs, December 1997, 35.

[7] Amitai Etzioni, “USA Can’t Impose Democracy on Afghans,” USA Today, October 10, 2001.

[8] W. Eubank and L. Weinberg, “Terrorism and Democracy: Perpetrators and Victims,” Terrorism and Political Violence 13, no. 1 (March 1, 2001): 156.

[9] Eubank and Weinberg, “Terrorism and Democracy.”

[10] Håvard Hegre, Tanja Ellingsen, Scott Gates and Nils Petter Gleditsch, “Toward a Democratic Civil Peace? Democracy, Political Change, and Civil War, 1816-1992,” American Political Science Review, no. 01 (March 2001): 42; Daniel Byman, The Five Front War: The Better Way to Fight Global Jihad (Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), 158–9.

[11] The 9/11 Commission Report, 135–7, 208, 332.

[12] United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Prewar Intelligence Assessments About Postwar Iraq (Washington, D.C., May 25, 2007), 103.

[13] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Prewar Intelligence, 100.

[14] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Prewar Intelligence, 93–4.

[15] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Prewar Intelligence, 97.

[16] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Prewar Intelligence, 4.

[17] National Intelligence Council, Regional Consequences of Regime Change in Iraq, January 2003, 30.

[18] National Intelligence Council, Principal Challenges in Post-Saddam Iraq, January 2003, 5.

[19] National Intelligence Council, Principal Challenges in Post-Saddam Iraq, 9.

Image Credit: Library of Congress